Much has been written about Sumatra, but few have presented the island as beautifully as the authors below. In 1921 Louis Couperus traveled across Sumatra as a special correspondent for the Haagsche Post and wrote down his impressions about Sumatra in the bundle Eastwards. The writing couple Laszlo Székely and Madelon Lulofs wrote inimitably about Sumatra, former governor Louis Constant Westenenk beautifully narrated about tigers and elephants and Sitor Situmorang and Rudy Kousbroek wrote unforgettable childhood memories.

Rudy Kousbroek:

“It is getting dark in the garden, but the flying dogs, which pass high in the sky, still catch light. This is not a dreamed or fantasy setting; it is real, or at least once it has been, it has existed, even beyond my memory. Where? Clearly, there is only one place in the world where such a scene has taken place: Indonesia. Such miracles are daily work in that island kingdom. Flying dogs. Insects that roared like airplanes. Kale on columns as high as church towers. A waterfall, a sulfur lake, warm rains that thunder, without warning, the drops so big that there is no more space – and then suddenly stop … Darkness that spreads as if someone is pouring East Indian ink (the name says it all) about a watercolor. Nights full of demonic noise, with flies flying through the air burning. Smoking mountains. A roof full of monkeys. Mornings fresh and quiet like the birth of the world, pink and pearl … Life in paradise, childhood memories. ” [1]

Rudy Kousbroek in Poeloe Radja early 1930s. [2]

The island of Sumatra is almost eight hundred kilometers long and the sixth largest island in the world. A mountain range runs from north to south across the island covered in vast jungle. The Sumatran tiger, elephants, rhinoceroses and orangutans and countless other animals live here. The island is still home to one of the largest pristine primary rainforests in the world with a wide variety of flora and fauna.

Unlike Java and the Moluccas, most of Sumatra only came under effective Dutch government in the second half of the nineteenth century. With only Lampong in the south and a number of strongholds along the coast such as Padang and Palembang, the Dutch still had no control over the interior. Even Lake Toba was unknown at the beginning of the 19th century, as Marsden wrote in his 1811 History of Sumatra:

a lake, one of great extent, but unascertained, in the Batta country. [3]

Sabang

Sabang on the island of Weh, is the extreme point of Sumatra and port where the large ocean liners could bunk coal. Louis Couperus went on a journey in 1921 – then still the Dutch East Indies – as a special correspondent of the Haagsche Post. Sabang was the first port in the Dutch East Indies where they disembarked. Couperus:

‘The coasts green and gold, the still young but rampant port city of Sabang with its black stacked coal sheds, make a special impression. That of the energetic, European effort, in a country and climate by the gods, not otherwise intended for mere dreamy laziness and idleness, but for nothing else. Sabang, we dock; I put my first foot on Sumatra’s ground. It is strange how such awareness can put you on. It is first a jetty, then a road between the black coal pile, then unexpectedly, the golden green tropical splendor of coconut palms after rainfall. Over the hills spread the mysterious jungle, the jungle. There is no wind, where is the wind of Poeloe Wei?’ [4]

Louis Couperus traveled from Sabang to the East coast of Sumatra, which is discussed in the second part. Then in part 3 the city of Medan, in parts 4 and 5 Brastagi and Lake Toba, in part 5 tigers and elephants and in the last part six West Sumatra, the land of the Minangkabau.

Louis Couperus at Lake Toba, right mrs. Couperus, left mrs. Westenenk, wife of governor Westenenk. [5]

[1] Kousbroek, R. Morgen spelen wij verder, p. 215, Meulenhoff Amsterdam, 1993.

[2] Foto: Rudy Kousbroek in Poeloe Radja. Fotokatern between pag. 116 en 117 in: Kousbroek, R. De vrolijke wanhoop. Meulenhoff, Amsterdam, 1993.

[3] Marsden, William, F.R.S. The History of Sumatra Containing an account of The Government, Laws, Customs, and Manners of the Native Inhabitants, with a Description of the Natural Productions, and a relation of the Ancient Political State of that Island. The Third Edition, with corrections, additions and plates. London, 1811: 14.

[4] Louis Couperus. ‘Oostwaarts’ in Haagse Post, 22 oktober 1921, 2 september 1922. In: Verzamelde Werken Ongewijzigde herdruk 1975 Uitgeverij G.A. van Oorschot, Amsterdam: 251.

[5] Foto: Loderichs, M.A., Buiskool, D.A. e.a. Medan, beeld van een stad Asia Major, Purmerend 1997: 31.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

The East Coast of Sumatra

Part 2

In 1823, John Anderson’s Mission to the East Coast of Sumatra was published. Anderson was impressed by Deli’s natural resources in Sumatra:

‘I do not know a country so productive as Delli, considering the number of its inhabitants; nor is there perhaps one on the face of the globe possessing so many natural advantages. The productions are numerous and valuable; and the bare mention of their names alone, would occupy a large space.’ [1]

At that time, the Batak were still an isolated population group with its own culture and traditions. In Anderson’s words:

‘Having no religion, they fear[ed] neither God nor man’. [2]

In the mid-nineteenth century, Sumatra’s East Coast was still partly “terra incognita”. However, a spectacular development took place in the following years.

Laszlo Székely:

“And where are you going?” He asked me. “To Sumatra.” “Yes, but to which part of Sumatra? To the East Coast or to the West Coast? “When I admitted that I really didn’t know, he told me I was lucky enough to come with the” Hercules “, which sailed to the East Coast, the only region with a great future. “Well, I said to Peter,” we’re definitely going to the right place. ” [3]

In 1937 the Hungarian Laszlo Székely (1892-1946) wrote the novel Van Oerwoud tot plantage (Tropic Fever) from which the above fragment originates. This highly autobiographical story took place in Sumatra between 1912 and 1924, when the Deli rubber plantations were still in the pioneering period. Szekely described the train journey from Belawan port to Medan city as follows:

“Nowhere a village or even a house. Not even a coconut tree. Only forest and swamp, lianas, monkeys, jungle, scrub, silence, dark patches of water. Suddenly, as if drawn with a ruler, a huge plantation. Locks in a straight line, in between paths, two meter high tobacco plants in endless straight rows. A pale green sea of leaves rocked as far as the eye could see. Everything carefully maintained, almost exaggerated. ….. Now one plantation followed another. The kampongs were no longer in the forest, but around the plantations. .. And suddenly we entered the station of the capital. Everywhere order and cleanliness. Beautiful stone buildings, an iron viaduct, a glass-covered lobby above the platform. Native and Chinese coolies carried the luggage, Malaysian and Chinese travelers poured out of the carriages, European railway officials in white uniforms and red caps walked up and down like peacocks between hens. A large square in front of the station. Shiny asphalt roads with mighty palms on both sides, beautiful bungalows with manicured gardens, strange flowers in bright colors … Fifty years ago this city did not even exist. Fifty years ago, here, where there are asphalt streets, red-roofed bungalows, clinging carriages and policemen, there was jungle, swamp and tigers, elephants and rhinoceroses. “ [4]

In 1863 Jacob Nienhuys, son of an Amsterdam tobacco merchant, came to Deli after being told of the high-quality tobacco from this region. In the words of Laszlo Székely:

“The world changed when the first white man, a Dutchman named Nienhuijs, came to Labuhan.” The Dutchman came unarmed and dressed only in a white suit but with unshakable willpower. He brought a gift to the Malaysian radja. He spoke to him long and convincingly. Talked to him about wealth, mighty palaces and piles of gold. And he established a first plantation. ” [5]

This Rajah was Sultan Mahmoud Perkasa Alam Shah from Deli. He gave Nienhuys permission to start a tobacco plantation just south of Laboehan (Labuhan) at the mouth of the Deli River. Szekely continued:

“But the indigenous people did not want to work on this. That’s why he recruited Chinese coolies from Singapore and Penang. A few European overseers also arrived, and then the fierce battle against the jungle began. Countless coolies died. The harvest was not large in the first year, but the Deli tobacco was discovered at the tobacco fair in Amsterdam. Tobacco like this had never been seen before. It was thinner than cigarette paper and softer than silk. The best wrapper in the world, they determined, and people fought over the few bales. The Sumatra tobacco became famous, adventurers, outlawed Russian counts and German officers who had to leave their country because of some dark affair, traveled to Sumatra and established a plantation. Where ancient forests had been, tobacco plantations were established, connected by narrow, swampy but passable roads. The colonial government sent officials, judges and police officers: colonization had started.” [6]

Laszlo Székely was married to Madelon Lulofs. The writing couple Szekely Lulofs described Deli in an inimitable way. In 1933, Madelon Szekely Lulofs published the novel Rubber, which immediately sparked a wave of excitement and protest because of the raw image that she portrayed Deli and the “affair” the married Madelon Lulofs had with Laszlo Szekely and why both had to leave Deli.

Madelon Lulofs en Laszlo Székely. [7]

Madelon Szekely Lulofs:

‘My father was a government official and we therefore stayed in various places in the Dutch East Indies. In my life, until 1930, Holland had never been anything but a country of leave and school time. The marriage kept me on rubber plantations of Sumatra’s East Coast for twelve years, from 1918 to 1930, and because this young district of Deli planters and pioneers was new to me, from this part of the Dutch East Indies eventually grew my first work, ‘Rubber’, ‘ Coolie’,’The other world’. But it wasn’t written before 1930, when I was in Europe for good and the insight and memories started to grow, about that, far away, at the equator. ” [8]

Madelon Székely-Lulofs foto with signature. [9]

Coolies

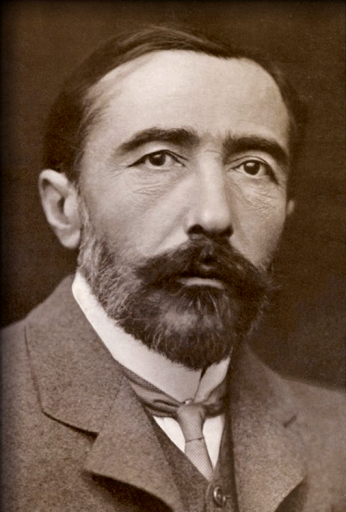

Thousands of Chinese, Javanese and Indians came to Sumatra’s East Coast to work as indentured laborers (coolies). The term coolie, probably a Tamil word, meaning ‘rent’ or ‘hired person’ was generally used for farm, plantation, mining and industrial workers. After the arrival of the major European agricultural companies, a massive Chinese immigration of plantation workers began. Joseph Conrad, who started out as a merchant seaman before becoming a famous author, personally witnessed the transport of Chinese coolies from Sumatra to South China and back.

Joseph Conrad:

The Nan-Shan was on her way from the southward to the treaty port of Fu-chau, with some cargo in her lower holds, and two hundred Chinese coolies returning to their village homes in the province of Fo-kien, after a few years of work in various tropical colonies. The fore-deck, packed with Chinamen, was full of sombre clothing, yellow faces, and pigtails, sprinkled over with a good many naked shoulders, for there was no wind, and the heat was close… and every single Celestial of them was carrying all he had in the world – a wooden chest with a ringing lock and brass on the corners, containing the savings of his labours: some clothes of ceremony, sticks of incense, a little opium maybe, bits of nameless rubbish of conventional value, a small hoard of silver dollars, toiled for in coal-lighters, won in gambling-houses or in petty trading, grubbed out of earth, sweated out in mines, on railway lines, in deadly jungle, under heavy burdens – amassed patiently, guarded with care, cherished fiercely. [10]

Joseph Conrad

Return to Ithaca

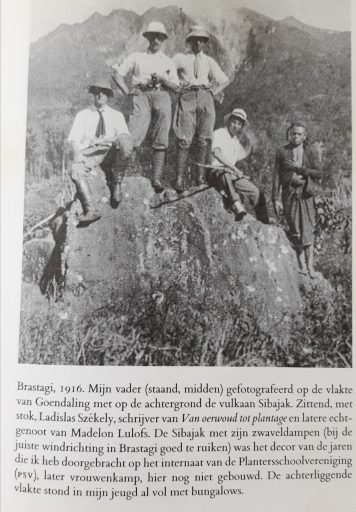

By the 1920s, there were more than two hundred tobacco, rubber, and palm oil plantations on the East Coast of Sumatra. Rudy Kousbroek wrote in his essay Back to Ithaca, about his father, a planter on Sumatra’s East Coast. His father came to work there in the same period as Laslzlo Szekely and knew him well. In the following quotation Rudy Kousbroek compares the ancient Greek story of the Ilias of Homer in which Odysseus returns to Ithaca to see his father with own feelings when he saw an old photo of his father on Sumatra. He replaces himself into Odysseus looking at his father.

Father of Rudy Kousbroek [11]

The Dutch East Indies, that was my father’s country. Here is a picture of him there, on Sumatra, a picture from long before my birth; he looks like I’ve never known him, young and slender, but still recognizable by his white toetoep (Closed collar white cotton suit), by his shoes, by his way of standing. I like everything about him, I view him with an ocean of love; he represents the Dutch East Indies to me, he is my Virgilius, my access to that part of the world: the country where I was born and raised and which is no longer there.

A thought for August 15: what would it be like if it still existed? What if there had never been war? If I could see him back there as he would be: an old planter, in the same environment? So the same picture actually, but half a life later? That image reminds me irresistibly of the return to Ithaca of Odysseus: also a return to his native soil, as it would be for me, but everything is still there – as I would like it so much – and then he goes looking to his father, Laërtes, who has grown old and does not know that his son has returned.

Laërtes is engaged in gardening – which is a reference to my father’s profession as a planter, which he still practices today – and in old garden clothes, so that Odysseus has difficulty recognizing him. Conversely, the father recognizes the son even less. Reading in the Odyssey, the last chapter, I am always amazed at how clear references to the island of Sumatra appear in the text. I quote..:

“Laërtes was still weeding the weeds in a bowed position when his glorious son spoke to him and said: ‘Old man, everything looks just as neat and I can see that you are a boss in gardening. Everything testifies to you care [that clearly refers to the Dutch East Indies, that care is still there]: the green plants, the fig trees, the vines, the olives, the pear trees, the vegetables. But (…) want to tell me – and do the truth – whose garden is this, which you maintain with such care? And I want to know this too: is this island where I ended up really Ithaca? “”

“Laërtes replied to him, and tears filled his eyes:” Stranger, this is indeed the island you hoped to find.” ” Then Odysseus makes himself known – “Father, it is me!” – but Laërtes has doubts and wants a sign of recognition. Breathlessly I read what follows, the evidence that Odysseus gives, details from his childhood on Ithaca that can only be known to him and his father: “… I can also call you in this garden all the trees that you gave me. I was still small, I followed you everywhere and asked questions. And you told me the name of everything that grew You gave me thirteen pear trees, ten apple trees, forty fig trees, fifty vines in rows, of different kind, so that there is no season that there be no fruits of any kind. “

When I read this I overcome with emotion. I hear my father’s voice mentioning the names of all Indian plants and fruit trees. This is the sign of recognition, all at once: the longing for my youth, for the country of origin, and for my father. I stare at the photo: his mind is in everything – the ground, the shadow under the leaves, the place where he stands [which is still there and which will always be there: its shape is still floating]. My father was an exception among the Deli planters: a lover of books and music, eloquent and well-read, a lover of the country – my father. [12]

Foto: Fotokatern tussen pag. 116 en 117 in: Kousbroek, R. De vrolijke wanhoop. Meulenhoff, Amsterdam, 1993

Foto: Rudy Kousbroek’s father standing in the middle in on the plain of Goendaling with the Sibayak volcano at the background in Brastagi. Sitting with stick Ladislas (Laszlo) Szekely, author of Van oerwoud tot plantage (Tropic Fever) and husband of Madelon Lulofs. The Sibayak was familiar to Rudy Kousbroek as he went to the Planters School (planters boardingschool) which later became a Japanese civil internment camp for women. Behind the foto in the years after many bungalows were build.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Anderson 1826: 35.

- Anderson 1826: 35.

- Székely Tropic Fever 1984: 25.

- Székely, Tropic Fever 1984: 42,43.

- Szekely, Tropic Fever 1984: 61.

- Szekely, Tropic Fever, 1984: 62,63.

- Foto: Okker, F. Tumult. Het levensverhaal van Madelon Székely-Lulofs. Uitgeverij Atlas Amsterdam/Antwerpen 2008. Fotokatern tussen pag. 96 en 97.

- Székely-Lulofs, Madelon in: Zóó leven wij in Indië samengesteld o.l.v. C.W. Wormser. Tweede druk. Van Hoeve, Deventer 1943.

- Foto: Okker, F. Tumult. Het levensverhaal van Madelon Székely-Lulofs. Uitgeverij Atlas Amsterdam/Antwerpen 2008. Fotokatern tussen pag. 192 en 193.

- Conrad, J. The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ / Typhoon / and other stories. Penguin 1973: 157,58.

- Kousbroek, R. Het Meisjeseiland. Zijn mooiste werk verzameld. Uigeverij Augustus Amserdam, 2011: 584.

- Rudy Kousbroek, augustus 2006 Fotosynthese, ‘Terug naar Ithaca’ in Het meisjeseiland . Zijn mooiste werk verzameld. Uigeverij Augustus Amserdam, 2011: 583-585.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dutch

Dutch